The Songlines

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

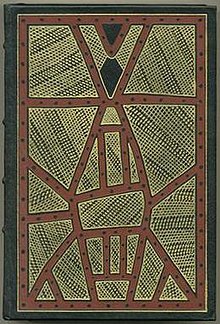

|

First edition | |

| Author | Bruce Chatwin |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Franklin Press |

Publication date | 1987[1] |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

The Songlines is a 1987 book written by British novelist and travel writer Bruce Chatwin about the songs of Aboriginal Australians and their connections to nomadic travel. A roman à clef that combines novel, travelogue, and memoir, Chatwin blends elements of fiction and non-fiction to describe a trip to Australia's Northern Territory in search of a better understanding of Aboriginal culture and religion, the Aboriginal land rights movement, and the Australian Outback more generally. The book is Chatwin's most famous work, a best seller upon publication in both the United States and United Kingdom.[2]

Synopsis

[edit]The book is centered around a British writer named "Bruce" that travels to Alice Springs, Australia to join a land surveyor mapping the location of a proposed 1,500 Kilometer rail line to be constructed from Alice Springs to Darwin, Australia. Specifically, the narrator befriends "Arkady" a local who is tasked by the rail company with conferring with local Aboriginals to understand which landscapes are considered sacred in Aboriginal culture and thus should be avoided. Arkady, Bruce and a group of Aboriginal locals travel in a Toyota Land Cruiser through Outback Australia, and the first half of the book chronicles these various encounters. Bruce eventually becomes stranded in small remote Aboriginal village for several weeks due to heavy rains, and spends his time musing on the nature of man as nomad and settler, connecting his Australian experiences with those of other nomadic cultures he experienced in his travels around the world. Chatwin develops a thesis about the primordial nature of Aboriginal song and its connections with the evolutionary conditions under which human populations evolved. The writing engages the hard conditions of life for present-day Indigenous Australians, including the fraught and contradictory relationship with White Australians, while appreciating the art and culture of the people for whom the Songlines are the touchstone of reality.

While the names are changed, most of the characters and places in the story are based on real-life counterparts, although Chatwin later claimed the book should be considered a work of fiction. [3] According to Chatwin's biographer Nicholas Shakespeare, Chatwin spent a total of 9 weeks in Central Australia, first in February of 1983 and returning again in March of 1984, ostensibly for an appearance at the Adelaide Writer's Festival. On this latter trip, Chatwin was accompanied in part by his friend and fellow writer Salman Rushdie where, among other things, they climbed Ayers Rock.[4] Chatwin was able to secure a permit to stay in the Aboriginal Village of Kintore for a period of two weeks, although he had difficulty speaking with the local residents due to barriers in language and his outsider status.[5] Preliminary work on the rail line from Alice Springs to Darwin was being planned by the federal government as early as 1981 and had been a major topic of debate in Australian politics during that time, although by mid 1983 the project had been officially cancelled (it eventually was completed in 2004). [6] [7] Friends and observers later surmised that the "fiction" label was largely a means to avoid questions about the veracity of various quotes and ideas presented in the work, especially around a topic as sensitive as Aboriginal mythology. [8]

After returning to England, Chatwin spent the next several years working to finish the book while struggling with the debilitating complications of what he (correctly) suspected was the HIV virus. Rushdie later remarked, "That book was an obsession too great for him, a monkey he carried around on his back. His illness did him a favour, got him free of it. Otherwise, he would have gone on writing it for ten years."[9]

Thesis

[edit]Chatwin asserts that language started as song, and in the Aboriginal Dreamtime, it sang the land into existence for the conscious mind and memory. As you sing the land, the tree, the rock, the path, they come to be, and the singers are one with them. Chatwin combines evidence from Aboriginal culture with modern ideas on human evolution, and argues that on the African Savannah, we were a migratory species hunted by a dominant feline predator. Our wanderings spread "songlines" across the globe (generally from southwest to northeast), eventually reaching Australia, where they are now preserved in the world's oldest living culture.

Reactions

[edit]The New York Times review praised the book as "[Chatwin's] bravest book yet", observing that it "engages the full range of the writer's passions" and that "each of his books has been a different delight [and] feast of style and form", but noted that Chatwin failed to bridge the "inevitable" "distance between a modern sensibility and an ancient one" in representing the Aboriginal relationship to their land, and did not sufficiently clearly establish the nature of the Songlines themselves, despite Chatwin's "quoting pertinently" from Giambattista Vico and Heidegger, and while acknowledging the difficulty of so doing, concluded that he ought to have "found some way to make the songs accessible" to the reader. Chatwin's "vision", though "exhilarating", could also at times seem "naive" and "unhistorical"; the review concluded that, nevertheless, Chatwin "remains one of our clearest, most vibrant writers".[10]

John Bayley, in a review for the London Review of Books, called the book "compulsively memorable", but observed the difficulty encountered by the anthropologist in his representation of a culture such as the Aboriginal one Chatwin dealt with: "describing [their] life and beliefs... falsifies them [and] creates a picture of unreality... seductively comprehensible to others"; Chatwin "makes no comparison or comment, and draws no conclusions, but his reader has the impression that anthropologists can't do other than mislead." He however praised "the poetry" of Chatwin's "remarkable pages"; and considered that "the book is a masterpiece".[11]

In The Irish Times, Julie Parsons, after consideration of the difficulties encountered by Chatwin—"born, raised and educated in the European tradition"—in apprehending the nature of the relationship between the Aborigines and the land on which they live, notes that as the reader follows his narrative, they "realise the impossibility of Chatwin's project. The written word cannot express this world", but the book is read nevertheless "with pleasure and fascination. We read it to learn how little we know."[12]

Rory Stewart, in The New York Review of Books, observed that the book "transformed English travel writing", praising his "concision" and "erudition", and acknowledging Chatwin's inspirational character and the view of The Songlines as "almost... a sacred text", leading Stewart and others to travel and "arrange... life and meaning"; he noted that whereas his own travels were at times "repetitive, boring, frustrating", "this is not the way that Chatwin describes the world", nor experienced it. Despite Stewart's conclusion that "today... [his] fictions seem more transparent" and that Chatwin's "personality... learning... myths, even his prose, are less hypnotizing", he considers that "he remains a great writer, of deep and enduring importance." Of particular note was Chatwin's representation of the Aboriginal people he encountered; despite the hardships of their daily existence—sickness, addiction, unemployment—"they are not victims... they emerge as figures of scope, and challenging autonomy."[13]

Literary references

[edit]The character Arkady refers to Australia as "the country of lost children". This was used as the title for Peter Pierce's 1999 book The Country of Lost Children: An Australian Anxiety.

See also

[edit]

- Ethnogeology

- Dreaming (Australian Aboriginal art)

- Aboriginal title on land rights

References

[edit]- ^ "The Songlines. - CHATWIN, BRUCE". www.antiqbook.com.

- ^ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. The Harvill Press. ISBN 1-86046-544-7. Page. 512

- ^ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. The Harvill Press. ISBN 1-86046-544-7 Page 512

- ^ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. The Harvill Press. ISBN 1-86046-544-7 Page 469 and 497.

- ^ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. The Harvill Press. ISBN 1-86046-544-7. Page. 499

- ^ "Preliminary work starts on 1500km Alice - Darwin link" Railway Gazette International April 1981 page 262

- ^ History of the railway AustralAsia Railway Corporation https://www.aarail.com.au/railway

- ^ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. The Harvill Press. ISBN 1-86046-544-7. Page. 481

- ^ Shakespeare, Nicholas (1999). Bruce Chatwin. The Harvill Press. ISBN 1-86046-544-7. Page. 48p

- ^ "Footprints of the Ancestors". archive.nytimes.com.

- ^ Bayley, John (July 9, 1987). "Writeabout". London Review of Books. 09 (13) – via www.lrb.co.uk.

- ^ Parsons, Julie. "In praise of older books: The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin (1987)". The Irish Times.

- ^ Stewart, Rory. "Walking with Chatwin".