Hurricane Iniki

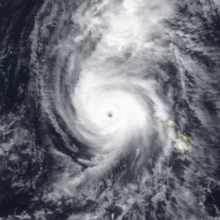

Hurricane Iniki at peak intensity south of Kauaʻi on September 11 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 5, 1992 |

| Dissipated | September 13, 1992 |

| Category 4 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 145 mph (230 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 938 mbar (hPa); 27.70 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 7 total |

| Damage | $3.1 billion (1992 USD) (Third-costliest Pacific hurricane on record; costliest in Hawaiian history) |

| Areas affected | Hawaii (particularly Kauaʻi) |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1992 Pacific hurricane season | |

Hurricane Iniki (/iːˈniːkiː/ ee-NEE-kee; Hawaiian: ʻiniki meaning "strong and piercing wind") was a hurricane that struck the island of Kauaʻi on September 11, 1992. It was the most powerful hurricane to strike Hawaiʻi in recorded history, and the only hurricane to directly affect the state during the 1992 Pacific hurricane season.[1] Forming on September 5, 1992, during tas the first hurricane to hit the state since Hurricane Iwa in the 1982 season, and the only known major hurricane to hit the state. Iniki dissipated on September 13, about halfway between Hawaii and Alaska.

Iniki caused around $3.1 billion (equivalent to $7 billion in 2023) in damage and seven deaths. This made Iniki, at the time, the costliest natural disaster on record in the state, as well as the third-costliest to hit the U.S. It struck just 18 days after Hurricane Andrew, the costliest tropical cyclone ever at the time, struck Florida.

The Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC) failed to issue tropical cyclone warnings and watches 24 hours in advance. The hurricane destroyed more than 1,400 houses on Kauaʻi and severely damaged more than 5,000. Though not directly in the path of the eye, Oʻahu experienced moderate damage from wind and storm surge.

Meteorological history

[edit]

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The origin of Iniki is unclear, but it may have begun as a tropical wave that exited the west African coast on August 18. It moved westward across northern South America and Central America, entering the eastern Pacific Ocean on August 28. On September 5, Tropical Depression Eighteen-E developed from the wave, about 1,700 miles (2,700 km) southwest of the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula, or 1,550 miles (2,490 km) east-southeast of Hilo.[1] Upon its formation, the depression had a ragged area of convection, and the National Hurricane Center anticipated minimal strengthening over the subsequent few days. This was due to the convective structure having poorly-defined outflow, or ventilation. Warm sea surface temperatures, 2–5° F (1–3° C) above normal, were considered a positive factor.[2][3][4] On September 6, the depression crossed 140° W, entering the area of warning responsibility of the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC).[1] On that day, the CPHC anticipated that the depression would dissipate within 24 hours, and ceased issuing advisories, but the depression reorganized on the next day, and warnings were reissued.[4] Steered by a subtropical ridge to the north, the depression continued westward, or slightly south of due west. On September 8, the CPHC upgraded the depression to tropical storm status, giving it the name Iniki, which is Hawaiian for a sharp and piercing wind.[1]

Iniki gradually intensified as its track shifted to the north. It moved around the western edge of the subtropical ridge, which was weakening due to an upper-level trough moving eastward from the International Date Line. Typically, the subtropical ridge keeps storms away from the Hawaiian islands. On September 9, Iniki strengthened into a hurricane, and the next day it passed about 300 miles (480 km) south of Ka Lae, the southernmost point of the Big Island of Hawaii. The hurricane slowed and curved toward the north while continuing to intensify. On September 10, a reconnaissance aircraft flew into Iniki, observing sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h), which is a major hurricane, or a Category 3 on the Saffir-Simpson scale. The approaching trough caused Iniki to accelerate to the north-northeast toward the western Hawaiian islands.[1]

On September 11, a reconnaissance aircraft observed maximum sustained winds of 145 mph (233 km/h), with gusts to 173 mph (278 km/h), making it a Category 4 hurricane. The flight also observed a minimum barometric pressure of 938 mbar (27.7 inHg), the lowest ever observed in the Central Pacific at the time. At that time, the hurricane was about 130 mi (210 km) southwest of Lihue. Iniki weakened slightly after its peak, and its eye made landfall on the southern coast of Kauai near Waimea with winds of 140 mph (230 km/h), making it the strongest hurricane on record to strike Hawaii. Iniki moved rapidly across the island, and about 40 minutes after landfall, it reemerged into the Pacific Ocean as it accelerated away from the state. The hurricane thereafter weakened, dropping to tropical storm status by September 13. That day, Iniki transitioned into an extratropical cyclone as it integrated with an approaching cold front about halfway between Hawaii and Alaska.[1]

Preparations

[edit]While Iniki was in its development stages, various tropical cyclone forecast models anticipated a range of possibilities for the hurricane's future trajectory, ranging from a landfall on the Big Island to a path to the west, away from the state. The hurricane initially followed a trajectory similar to other storms in the region, passing south of the state. The CPHC relied on the Miami-based National Hurricane Center for the models, and lacked a detailed analysis on each model run, which caused errors in forecasting. The agency also had limited satellite imagery and direct observations to track the hurricane. As such, the CPHC failed to issue tropical cyclone warnings and watches for the hurricane well in advance, although the agency warned for the potential of high surf. For several days before the disaster, the CPHC and the news media forecast Iniki to remain well south of the island chain.[4]

Two days before the storm struck, the Naval Western Oceanography Center on Oʻahu recommended that the United States Navy fleet at the Pearl Harbor Shipyard to start storm preparations. A few Naval facilities were evacuated, some ahead of official hurricane warnings from the CPHC.[4] Early on September 11, less than 24 hours before Iniki made landfall, the CPHC issued a hurricane watch for Kauaʻi, Niihau, and the northwestern Hawaiian islands to the French Frigate Shoals. A few hours later, the agency upgraded the watch to a hurricane warning for Kauaʻi and Niihau. A hurricane warning was later issued for Oʻahu, while a tropical storm watch was issued for the islands of Maui County. Warning sirens blared on Kauaʻi and Oʻahu to warn the public of the approaching storm. The hurricane warning for Kauaʻi was downgraded to a tropical storm warning after Iniki departed the island, causing some confusion whether there was another storm approaching the area. Reports about the storm were disseminated by radio, newspapers, and news stations. After the hurricane warnings were issued, TV stations began 24-hour coverage of the storm. Residents responded well to the hurricane, in part due to the scenes of destruction from Hurricane Andrew in south Florida three weeks earlier. Iniki nearly struck the Central Pacific Hurricane Center in Honolulu. Had it hit there, Iniki, along with Hurricane Andrew and Typhoon Omar, would have struck each of the three National Weather Service offices responsible for tropical cyclone warnings within a two-month period.[4]

In response to the approaching hurricane, about 38,000 people evacuated to public shelters, including 8,000 on Kauaʻi and 30,000 people in Oʻahu. On Kauaʻi, school was canceled, and the traffic was light during the evacuation, with streets clear by mid-morning. Rather than send tourists to public shelters, two major hotels kept their occupants in the buildings during Iniki's passage of Kauaʻi.[5] Some residents rode out the hurricane in their homes. According to a post-storm survey, no one on the island did not hear about the impending storm.[4] On Oʻahu, all schools, and most businesses, closed during the storm's passage. Only critical government employees worked during the storm. Officials opened 110 public shelters on Oʻahu, including some schools meant for refuge only; this meant they provided no food, cots, blankets, medications, or other comfort items. Roughly one-third of Oʻahu's population participated in the evacuation, though many others went to the house of a family member or friend for shelter. Officials assessed that the evacuations went well, beginning with the vulnerable coastal area. For those in need, vans and buses gave emergency transportation, while police occupied certain overused intersections. The two main problems during the evacuation were lack of parking at shelters and exit routes for the coastlines.[5] On the Big Island, officials ordered residents within 300 ft (91 m) of the coastline to evacuate to higher ground.[4]

Impact

[edit]| Rank | Cyclone | Season | Damage | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Otis | 2023 | $12–16 billion | [6] |

| 2 | Manuel | 2013 | $4.2 billion | [7] |

| 3 | Iniki | 1992 | $3.1 billion | [8] |

| 4 | John | 2024 | $2.5 billion | [9] |

| 5 | Odile | 2014 | $1.25 billion | [10] |

| 6 | Agatha | 2010 | $1.1 billion | [11] |

| 7 | Hilary | 2023 | $915 million | [12] |

| 8 | Willa | 2018 | $825 million | [13] |

| 9 | Madeline | 1998 | $750 million | [14] |

| 10 | Rosa | 1994 | $700 million | [15] |

Hurricane Iniki was the costliest hurricane ever to strike Hawaii, causing $3.1 billion in damage. That made it the third-costliest U.S. hurricane at the time, behind Hurricane Hugo in 1989 and Hurricane Andrew in August 1992, one month earlier.[8] It was the first significant hurricane to threaten the state since Hurricane Iwa ten years earlier.[5] Iniki affected all of Hawaii with high waves and strong winds, with the worst impacts on Kauaʻi.[4] Seven people died during the hurricane – three on Kauaʻi, two offshore, and two on Oahu. The low death toll was likely due to well-executed warnings and preparation.[4] Of the offshore deaths, two were Japanese nationals who died when their boat capsized south of Kauaʻi.[1] There were also around 100 storm-related injuries throughout the state, some of which occurred during the hurricane's aftermath.[4]

Kauaʻi

[edit]Hurricane Iniki made landfall on south-central Kauaʻi and moved across the island in 40 minutes.[1] Much of the island experienced sustained winds of 100 to 120 mph (160 to 190 km/h). Wind gusts were estimated at 175 mph (282 km/h) at landfall. There was an uncalibrated wind gust of 217 mph (349 km/h) at Makaha Ridge, at the top of a cliff. A station at Makahuena Point recorded a gust of 143 mph (230 km/h).[4] Based on the island's damage patterns, meteorologist Ted Fujita estimated there were as many as 26 microbursts, sudden downdrafts of wind capable of reaching 200 mph (320 km/h). There were also two mini-swirls, small localized swirls within the eyewall. In general, the winds descending the island's mountains were more damaging than the upslope winds.[16] In addition to its strong winds, Iniki lashed the southern Kauaʻi coastline with a 4 to 6 m (13 to 20 ft) storm surge, or rise in water. On top of the surge, the hurricane produced wave heights of 17 ft (5.2 m), with a high water mark of 22.2 ft (6.8 m) at Waikomo Stream near Koloa.[4] The high waves left a debris line more than 800 feet (240 m) inland. Because it moved quickly through the island, there were no reports of significant rainfall.[5]

Iniki's passage left extensive damage throughout Kauaʻi, with 14,350 homes damaged to some degree. Only the western part of the island was not severely damaged. Three people died on the island – one due to flying debris, one to a collapsed house, and one of a heart attack. Across Kauaʻi, Iniki destroyed 1,421 houses,[4] including 63 that were lost from the high waves and water. It also severely damaged 5,152 homes, while 7,178 received minor damage,[1] which left more than 7,000 people homeless.[17] High waters damaged several hotels and condominiums along the island's southern shore.[4] A few were restored quickly, but some took several years to be rebuilt. One hotel—the Coco Palms Resort famous for Elvis Presley's Blue Hawaii—never reopened.[18] Hurricane Iniki's making landfall during daylight hours, combined with the popularity of camcorders, led many Kauaʻi residents to record much of the damage as it occurred. The footage was later used to create an hour-long video documentary.[19] Commercial air service was suspended.[20]

Iniki's high winds also downed 26.5% of the island's transmission poles, 37% of its distribution poles, and 35% of its 800-mile (1,300 km) distribution wire system. The entire island lacked electricity and television service for an extended period.[17] Electric companies restored only 20% of the island's power service within four weeks of Iniki, while other areas had no power for three to four months. Also affected by the storm was the agricultural sector.[1] Much of the sugar cane was already harvested,[17] but what was left was severely damaged. The winds destroyed tender tropical plants like bananas and papayas and uprooted or damaged fruit and nut trees.[1] The high winds stripped much of Kauai of its vegetation, wrecking sugar cane fields as well as fruit and nut trees.[4]

Among those on Kauaʻi was filmmaker Steven Spielberg, who was preparing for the final day of on-location shooting of the film Jurassic Park. He and the 130 of his cast and crew remained safely in a hotel during Iniki's passage.[21][22] According to Spielberg, "every single structure was in shambles; roofs and walls were torn away; telephone poles and trees were down as far as the eye could see." Spielberg included footage of Iniki battering the Kaua'i coastal walls as part of the completed film, where a tropical storm is a pivotal part of the plot. Members of the film's crew helped to clear some of the debris off of nearby roads.[21]

Elsewhere

[edit]East of the hurricane's landfall, Oʻahu received tropical storm-force winds during Iniki's passage along its southwestern coast, with an island-wide peak gust of 82 mph (132 km/h) in Waianae. The outer rainbands of the hurricane spawned an F1 tornado in Nānākuli, also on Oʻahu. Along western Oahu, Iniki produced a 2 to 4 ft (0.61 to 1.22 m) surge, with 17 ft (5.2 m) waves recorded near Mākaha.[4] Prolonged periods of high waves severely eroded and damaged the southwestern coast of Oʻahu, with the areas most affected being Barbers Point through Kaʻena.[1] The Waiʻanae coastline experienced the most damage, with waves and storm surge flooding the second floor of beachside apartments.[23] In all, Hurricane Iniki caused several million dollars in property damage,[5] and two deaths on Oʻahu.[1]

High swells affected the southwestern coasts of Maui and the Big Island, which damaged boats, harbors, and coastal structures.[4] On the Big Island, seas of 10 ft (3.0 m) were reported, along with 40 mph (65 km/h) winds.[24] The high waves damaged 12 homes on the Big Island.[16] In Honokōhau Harbor, three or four sailboats were tossed onto the rocks and one trimaran at another harbor was sunk. A beach near Napoʻopoʻo on Kealakekua Bay lost some sand and to this day has never been the same.[25]

Aftermath

[edit]| Hurricane | Season | Wind speed | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Otis | 2023 | 160 mph (260 km/h) | [26] |

| Patricia | 2015 | 150 mph (240 km/h) | [27] |

| Madeline | 1976 | 145 mph (230 km/h) | [28] |

| Iniki | 1992 | [29] | |

| Twelve | 1957 | 140 mph (220 km/h) | [30] |

| "Mexico" | 1959 | [30] | |

| Kenna | 2002 | [31] | |

| Lidia | 2023 | [32] |

Immediately after the storm, many were relieved to have survived the worst of the hurricane; their complacency turned to apprehensiveness due to lack of information, as every radio station was out and no news was available for several days. Because Iniki knocked out electrical power for most of the island, communities held parties to consume perishable food from unpowered refrigerators and freezers, and many hotels prepared and hosted free meals to use up their perishables. Though some food markets allowed those affected to take what they needed, many Kauaʻi citizens insisted on paying. In addition, entertainers from all of Hawaiʻi, including Graham Nash (who owns a home on the north shore of Kauaʻi) and the Honolulu Symphony, gave free concerts for the victims.[18]

Three days after Iniki struck Hawaii, the NOAA Assistant Administrator for Weather Services directed that a disaster survey team investigate the warnings and responsiveness to the hurricane.[4] The passages of Iwa and Iniki within a ten-year period increased public awareness of hurricanes in Hawaii.[16]

Jurassic Park was being filmed at the time; the sets used for the deleted scene where Mr. Arnold goes to the shed to turn the power on were destroyed, and the cast and crew took shelter in a hotel. Shots of Iniki made it into the film. Looting occurred in Iniki's aftermath, but it was very minor. A group from the Army Corps of Engineers, who experienced the looting during Hurricane Andrew just weeks before, were surprised at the overall calmness and lack of violence on the island. Electrical power was restored to most of the island about six weeks after the hurricane, but students returned to Kauaʻi public schools two weeks after the disaster. Kauaʻi citizens remained hopeful for monetary aid from the government or insurance companies, but after six months they felt annoyed by the lack of help.[18] But the military effectively provided aid for their immediate needs, including MREs (meals ready to eat), and help arrived before local officials requested aid.[33]

By four weeks after the hurricane, only 20% of power was restored on Kauaʻi, following the island-wide blackout.[1] Amateur radio proved extremely helpful during the three weeks after the storm, with volunteers coming from neighboring islands as well as from around the Pacific to assist in the recovery. There was support of local government communications in Lihue in the first week of recovery[23] as well as a hastily organized effort by local operators to assist with the American Red Cross and their efforts to provide shelters and disaster relief centers across Kauaʻi.[34]

In the months after the storm, many insurance companies left Hawaiʻi. To combat this, Governor John D. Waihee III enacted the Hurricane Relief Fund in 1993 to help unprotected Hawaiʻi residents. The fund was never needed for another Hawaiʻi hurricane, and it was eliminated in 2000, when insurance companies returned to the island.[35]

Iniki ravaged multiple islands' native forest bird population.[36] It is also thought that the storm blew apart many chicken coops, some possibly used to house fighting chickens; this caused a dramatic increase in feral chickens roaming Kauaʻi.[37]

Due to the storm's impact, the World Meteorological Organization retired the name Iniki after the 1992 season; it will never again be used for a Central Pacific tropical cyclone. It was replaced in the basin's naming rotation with Iolana.[38][39]

In popular culture

[edit]The events and survivor accounts of the hurricane were featured in an episode of The Weather Channel docuseries Storm Stories, "Iniki Jurassic",[40] the sixth episode of the GRB Entertainment docuseries Earth's Fury (also known as Anatomy of Disaster outside the U.S.), "Hurricane Force",[41] the fourth episode of the 2008 Discovery Channel reality television series Destroyed in Seconds,[42] the 1996 Fox television special When Disasters Strike, and the 11th episode of the 1999 reality television series World's Most Amazing Videos.[43]

See also

[edit]- Tropical cyclones in 1992

- List of Category 4 Pacific hurricanes

- List of Hawai'i hurricanes

- List of Pacific hurricanes

- List of retired Pacific hurricane names

- Typhoon Higos (2002) – a storm that took a very similar trajectory to that of Iniki, albeit thousands of miles west of Hawaii, becoming one of the strongest typhoons to strike Tokyo

- Hurricane Lane (2018) – another powerful storm that threatened to strike Hawaii as a strong hurricane, but instead turned westward out to sea, bringing record amounts of rainfall to the islands

- Hurricane Walaka (2018) – took a similar track, making a 90° northward turn under the influence of an upper level trough, but stayed to the west of the main Hawaiian islands

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Central Pacific Hurricane Center (1993). The 1992 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season (PDF) (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 24, 2003.

- ^ Miles B. Lawrence (September 5, 1992). Tropical Depression Eighteen-E Discussion 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Max Mayfield (September 5, 1992). Tropical Depression Eighteen-E Discussion 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Natural Disaster Survey Report: Hurricane Iniki (PDF) (Report). April 1993. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e US Army Corps of Engineers (1993). "Hurricane Iniki Assessment" (PDF). US Military. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2006.

- ^ Reinhart, Brad; Reinhart, Amanda (March 7, 2024). "Hurricane Otis – Tropical Cyclone Report (EP182023)" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. University Park, Florida, United States: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 1–39. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Jakubowski, Steve; Krovvidi, Adityam; Podlaha, Adam; Bowen, Steve. "September 2013 Global Catasrophe Recap" (PDF). Aon Benfield. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ^ a b Costliest U.S. Tropical Cyclones Tables Update (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. January 12, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 27, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ^ "Sheinbaum pledges US $400M reconstruction package for Acapulco, calls for private sector's support". Mexico News Daily. November 20, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ Albarrán, Elizabeth (December 10, 2014). "Aseguradores pagaron 16,600 mdp por daños del huracán Odile" [Insurers Paid 16,600 MDP for Hurricane Odile Damages]. El Economista (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ Beven, Jack (January 10, 2011). Tropical Storm Agatha (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^ "KCC estimates privately insured loss for Hurricane Hilary at $600m". Reinsurance News. August 29, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ Navarro, Myriam; Santos, Javier (November 11, 2018). "Ascienden a $10 mil millones los daños que causó 'Willa' en Nayarit" [The damages caused by 'Willa' in Nayarit amount to $10 billion]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Archived from the original on January 15, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- ^ "South Texas Floods: October 17–22, 1998" (PDF). United States Department of Commerce. 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2007.

- ^ "Floods in Southeast Texas, October 1994" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. January 1995. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- ^ a b c Charles H. Fletcher III; Eric E. Grossman; Bruce M. Richmond; Ann E. Gibbs (2002). Atlas of Natural Hazards in the Hawaiian Coastal Zone (PDF) (Report). United States Geologic Survey. pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b c Unknown (1992). "Broadcast Journalism: Write to the Bite". Unknown. Archived from the original on February 16, 2012. Retrieved March 13, 2006.

- ^ a b c Anthony Sommer (2002). "The people of Kauai lived through a nightmare when the powerful storm struck". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Archived from the original on March 11, 2006. Retrieved March 13, 2006.

- ^ "ドッグフードにある栄養素". www.video-hawaii.com. Archived from the original on June 22, 1997. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "Big Waves at Waikiki but Oahu Is Mostly Spared". The New York Times. September 13, 1992. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ a b Shay, Don; Duncan, Jody (June 1993). The Making of Jurassic Park. Ballantine Books. pp. 85–87. ISBN 0-345-38122-X.

- ^ Al Kamen (September 13, 1992). "Hawaii Hurricane Devastates Kauai". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved March 13, 2006.

- ^ a b Ron Hashiro (1993). "Hurricane Iniki Rallies Amateurs". American Amateur Radio Relay League, Inc. Archived from the original on August 2, 2015. Retrieved March 13, 2006.

- ^ Al Kamen (September 13, 1992). "Hawaii Hurricane Devastates Kauai: Iniki Blamed For 3 Deaths, Scores of Injuries". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ "Big Island Hawaii Beaches". big-island-bigisland.com. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- ^ Brown, Daniel; Kelly, Larry (October 25, 2023). Hurricane Otis Tropical Cyclone Update (Report). Miami, Florida. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ Kimberlain, Todd B.; Blake, Eric S.; Cangialosi, John P. (February 1, 2016). Hurricane Patricia (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Gunther, Emil B. (April 1977). "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1976". Monthly Weather Review. 105 (4). Eastern Pacific Hurricane Center: 508–522. Bibcode:1977MWRv..105..508G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1977)105<0508:EPTCO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ The 1992 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season (PDF) (Report). Honolulu, Hawaii: Central Pacific Hurricane Center. 1993. Retrieved November 24, 2003.

- ^ a b Blake, Eric S; Gibney, Ethan J; Brown, Daniel P; Mainelli, Michelle; Franklin, James L; Kimberlain, Todd B; Hammer, Gregory R (2009). Tropical Cyclones of the Eastern North Pacific Basin, 1949-2006 (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 11, 2024. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ Franklin, James L. (December 26, 2002). Hurricane Kenna (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Bucci, Lisa; Brown, Daniel (October 10, 2023). Hurricane Lidia Intermediate Advisory Number 31A (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ^ J. Dexter Peach (1993). "What Hurricane Andrew Tells Us About How To Fix FEMA". United States General Accounting Office. Archived from the original on July 8, 2006. Retrieved March 18, 2006.

- ^ Greg Pool (1993). "Iniki and the American Red Cross". Worldradio. 22 (12): 1, 18–20. Archived from the original on January 10, 2005. Retrieved December 17, 2007.

- ^ "State should keep hurricane fund intact for next disaster". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. 2001. Archived from the original on September 22, 2005. Retrieved March 18, 2006.

- ^ "Hurricane Hell – Kauai Forest Bird Recovery Project". kauaiforestbirds.org. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ "Something's killing off Kauai chickens". Honolulu Advertiser. 2007. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- ^ "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclone Name History". Atlantic Tropical Weather Center. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "Tropical cyclone names". Exeter, Devon, UK: Met Office. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "Iniki Jurassic". Storm Stories. 2009. The Weather Channel. Retrieved May 21, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Hurricane Force". Anatomy of Disaster. Season 1. Episode 6. 1997. The Learning Channel. Retrieved May 21, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Hurricane Slams Hawaii. Discovery Channel. 2008. Retrieved May 21, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Episode 11". World's Most Amazing Videos. Season 1. Episode 11. 1999. NBC. Retrieved May 21, 2021 – via YouTube.

External links

[edit]